Four years ago, I went to the Westport Health Department on Bayberry Road to get a Tine Test. I was happy, of course, to learn I didn’t have TB, but also because it now allowed me to begin volunteering at Bedford Hills Women’s Correctional Facility. More recently I’ve begun visiting York Correctional Facility in Connecticut, and hopefully soon, the Federal prison in Danbury.

I had always wanted to volunteer and give back. I’d done small things here and there; some things fit, others didn’t but nothing on a regular basis. First my kids were young and needed my time. Then they were older and needed more of my time. I was working. I was writing. But now I was ready to find the right place, only I never thought I’d happen upon it by writing a story.

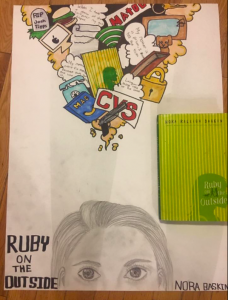

In 2014, before I wrote Ruby on the Outside I knew next to nothing about the issues of mass incarceration in the United States, when I cavalierly attended a charity function with Dr. Jill Becker, my college roommate and BFF, who is on the board of an organization called Rehabilitation Through the Arts (RTA.)

After a tour of the estate, hors d’oeuvres, and polite schmoozing, the event began. One after the other, speakers stood up and told their story.

A formerly incarcerated man described what it meant to discover art for the first time in prison.

“Art allows you to think differently, so you can behave differently, so you can get different results…to me, that’s what the definition of rehabilitation means.” Kenyatta Hughs (RTA)

A volunteer actress from New York City spoke about her experience at Sing Sing, the men’s prison in Ossining.

And finally, Katherine Vockins, the president of RTA spoke — so eloquently —about this organization she had helped start because, she said, “Through the arts, we’re opening their eyes to self-discipline and self-knowledge, presentation, delayed gratification, and nonviolent conflict-resolution.”

By the end of the afternoon I learned there are 2.2 million people behind bars in the United States— more than any other country in the world — in greatly disproportion demographic numbers: African Americans and Hispanics make up approximately 32% of the U.S. population, they comprised 56% of all incarcerated people.

And there are 10 million children in the United States who have experienced the loss of a mother, or father, or both because of our broken criminal justice system.

And that’s when the story became very personal to me.

My mother died when I was three and a half and whether she fully intended to or not, she successfully took her own life. In that moment, her choice, left me motherless and created an experience which has effected every single day of the rest of my life, but one I could not talk about. One I thought no one else shared.

Their story wasn’t my story, but it was my story. The shame, the secrecy, the loneliness. The profound confusion: How do you reconcile being the daughter of a mother who was not a good mother? How can you love someone who brought such pain to your life? Can you ever forgive your mother, forgive yourself?

If I was going to write this book — which the more I listened and learned the more I was driven to do it– I would be both healing myself and helping to lift a stigma I understood very well.

Katherine Vockins suggested I talk to Emani Davis, who had been one of the young subjects in a non-fiction book entitled, All Alone In the World by Nell Bernstein and was now a mother herself. A few weeks later, Emani and I spent the afternoon talking, after which I was even more convinced I could write this story. That I should write this story.

There was a still a long journey I had to take in order to bring Ruby to the pages of my book. We traveled together in a way I couldn’t do when I was Ruby’s age. Now, as a mother myself, and a wounded and extremely flawed human being, I was able to become, not only Ruby, but also the character of her mother. If I couldn’t have entered both experiences with compassion, I wouldn’t have written this book, or any other for that matter.

But although the emotional truth was authentic, I needed to do a lot more research for the external, factual story. Basically, I had to visit a prison without actually having any one in prison to be visiting. The chances of being a writer allowed into a prison are slim to none. I drove across the RFK bridge to Queens and met the remarkable Sister Tesa at Hour Children, an organization that helps children and incarcerated mothers remain connected, and assists the mothers when they re-enter society and their home lives.

There, I also met Alessandra Rose who told me she’d try to get permission for me to visit Bedford Hills, but there were no guarantees. At all. It took a lot of patient waiting, then one day I got the called straight from DOCCS (Department of Corrections and Community Supervision) in Albany.

“Nora Baskin?… You want to visit Bedford Hills. ..Be there. Friday. 9a.m. Don’t wear green.”

The black iron bars, the metal detectors and wands, the guards, the sign in, the invisible hand stamp, the twisting barbed wire, the open space visiting room, the numbered tables, the vending machines lined up against the far wall, the warm and friendly Hour Children visiting center.

I wrote it all down and I began my story.

As an artist I’ve always believed that after doing the initial research, the writing itself belonged only to me. But this time, I felt compelled to ask Kelli Phelan, Hour Children Youth Coordinator, who herself had once been incarcerated, one question: “Is there is anything you really feel I should, or should not include in my story.”

Maybe I was a little surprised when she quickly answered, yes.

“Please do not make your character a bad kid. Everyone assumes if you have a parent in prison, you’re bad too, and you’re going to go down the same path and it’s not true.”

Her words impacted my whole story in a way I never expected, and Ruby was born.

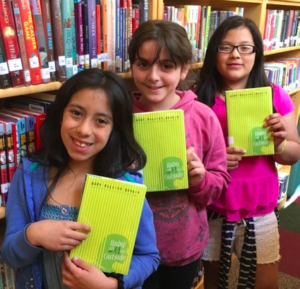

I mailed my finished manuscript to Kelli, who provided me with a reading group of 12-16 year-olds. I spent the afternoon listening to their feedback and I made several ever so tiny, and ever so important changes.

When I return to work in prison now, it is not for research. Not as writer and I am most decidedly not looking for a story. Besides, part of my orientation was about the strict policy of confidentiality and breaking it can lead to permanent expulsion.

All of this freed me in a powerful way, knowing fully that my time inside those walls was now only about helping others to find their voice and to heal.

Writing has always been a path to understanding my life and making sense of a world that often makes no sense at all. But never lose sight that it is also about seeking the truth, and if you are lucky enough to stumble upon it, just nod, and say thank you.

Gabi Coatsworth

March 27, 2019 - 1:56 am ·This is wonderful, Nora. Are you teaching writing in prisons?